Linkbox med materiale fra Tidslinjen om vigtigste år i Folkerepublikken Kinas historie efter 1949.

Tidsskriftcentret, september 2009

Opdateret, Socialistisk Bibliotek, september 2024.

Indhold: (datoer på Tidslinjen)

- 1. oktober 1949: Folkerepublikken grundlægges

- Januar 1958: “Det store spring fremad”-kampagnen

- August 1966: Kulturrevolutionen tager sin begyndelse

- 9. september 1976: Mao Zedong dør

Se også på Socialistisk Bibliotek:

- Tidslinjen: 1. juli 1921 om dannelsen af Kinas Kommunistiske Parti.

- Tidslinjen: 12. april 1927 om den kinesiske revolutions nederlag.

- Tidslinjen: 16. oktober 1934 om Den Lange March.

- Tidslinjen 19. februar 1997 om Deng Xiaoping.

- Tidslinjen 30. december 2002 om Wang Fanxi.

- Linkbox: Den Himmelske Freds Plads, 1989

- Tidslinjen 21. september 2014 om ‘Paraplyrevolutionen’ i Hong Kong + protesterne i 2019.

- Linkbox: China and Capitalism. Om Kinas nyere udvikling.

* * * * * * * * *

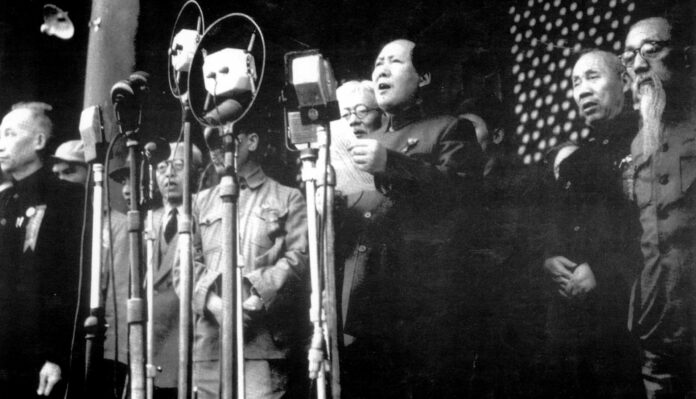

Folkerepublikken Kina: 1. oktober 1949

Kinesiske Folkerepublik grundlægges. “1/3 af Jordens overflade er kommunistisk”.

Se:

- Kina (Leksikon.org)

- Chinese Communist Revolution (Wikipedia.org)

- History of the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1976 (Wikipedia.org)

- Chinese Communism (Marxists Internet Archive)

- Material om utvecklingen i Kina (Marxistarkiv.se)

Kinas revolution i 1949. Af Adrian Budd (Socialistisk Arbejderavis, nr.375, 1. oktober 2019). “Revolutionen var ikke socialistisk, men den gav løfte om at forberede vejen for national befrielse og udvikling.”

Kina 60 år: Socialistisk revolution, kapitalistisk genopretning. Af Chris Slee (Socialistisk Information, 10. oktober 2009). “Revolutionens tidlige år skabte store sociale forbedringer for den forarmede befolkning. Helbreds – og uddannelsesniveauet blev højnet væsentligt.”

Kina 1949: Folkets revolution? Af Charlie Hore (Internationale Socialisters Forlag, 1989, 38 s.; online på Marxisme.dk). “Kinas ‘socialisme’ var en myte lige fra starten.”

Maos vej til magten. Af Tony Cliff (Kap. i Den afbøjede permanente revolution, 1963; online på Marxisme.dk). “Maos erobring af byerne afslørede mere end noget andet kommunistpartiet komplette adskillelse fra den industrielle arbejdeklasse.” Scroll ned.

In English:

Maoist China. Part 93 in Neil Faulkner: A Marxist History of the World (Counterfire, 16 September 2012). “After the revolution of 1949, the Chinese Communists resorted to state capitalism to force the country’s industrialisation. The consequences were disastrous.”

The Longest Night. By Gregory Benton (Anticapitalist Resistance, 25 November 2024). From Gregory Benton and Yang Yang’s book The Longest Night: Three generations of Chinese Trotskyists i Defeat, Jail, Exile and Diaspora (Brill, 2024, 1235 p.).”… this sequel to Prophets Unarmed [2015] delves into the tumultuous journey of Chinese Trotskyism after 1949, tracing its evolution through defeat, exile, and diaspora, while showcasing the enduring relevance of its revolutionary ideals through memoirs, theoretical writings, and historical analyses; this extract is taken from the introduction written by Benton.”

The Left in China: A Political Cartography. By Rob Hoveman (Socialist Worker, Issue 2845, 9 March 2023). Review of Ralf Ruckus book (Pluto Press, 2023, 240 p.). “Ralf Ruckus’s new book chronicles workers’ struggles against the Chinese Communist Party regime.”

China 1949: Year of Revolution. By Sean Ledwith (Counterfire, January 13, 2022). Review of Graham Hutchings’ book (Bloomsbury, 2021, 336 p.). “As China 1949 shows, the CCP victory of that year enabled the country’s rise to global power status, but it was not a workers’ revolution.”

On Contradiction: Mao’s party-substitutionist revolution in theory and practice. Part 1-4. By Richard Smith (New Politics, June 7 – July 29, 2022). “Explaining and debunking the theory and practice of Maoism.”

The Stalinist history of Maoism. By Paul Hampton (Solidarity & Workers’ Liberty, Issue 617, 6 December 2021). “Socialists trying to understand the 1949 Chinese revolution have to ask some key questions: which social agents overthrew the old regime, who led them and who ruled afterwards? The short answers are that the Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) won the civil war against the Guomindang, it was led by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and it was the CCP that ruled henceforth. Much then turns on the character of CCP in 1949.”

China 1949: What about the workers? By Paul Hampton (Solidarity & Workers’ Liberty, Issue 614, 7 November 2021). Review of Graham Hutchings’, China 1949: Year of Revolution (Bloomsbury, 2021, 336 p.). “Hutchings describes the takeover in 1949, using a wide range of Chinese and English-language sources. The book combines careful research with a highly readable narrative. It does not delve into why the CCP won, nor does it tackle the social nature of the new regime. However it makes clear that the takeover was not carried out by the Chinese working class.”

China’s revolution at 70: reality trumps myths (Socialist Review, Issue 450, October 2019). “As China launches its official celebrations marking 70 years since the revolution of 1949, Adrian Budd looks at the longer context of what was a national revolution, far from any vision of communism.”

The Chinese Revolution at seventy. By Dennis Kosuth (Jacobin, October 2, 2019). “The Chinese revolution turned seventy this week. If you were looking for reflection on the meaning of that revolution today, you wouldn’t find it in mainstream media coverage.”

1949 — Mao & the Chinese revolution. By Tomáš Tengely-Evans (Socialist Worker, Issue 2673, 24 September 2019). “Seventy years ago revolution in China threw off the rule of landlords and struck a blow to Western imperialism. But it wasn’t a socialist revolution, and its aims were not to put people in power.”

Revolution, capitalist restoration and class struggle in China. By Chris Slee (Links: International Journal of Socialist Renewal, February 24, 2019). “The transition to socialism was hindered both by objective conditions (including the backwardness of China and the pressures of imperialism), and by the bureaucratic nature of the CP.”

Demystifying Maoism. By Dan La Botz (New Politics, June 15, 2016). Review of Elliott Liu, Maoism and the Chinese Revolution: A Critical Introduction (PM Press, 2016, 148 p.). “Elliott Liu has written an excellent little book that examines Mao Tse-Tung’s role in the Chinese Revolution in an attempt to find out what Maoism really represented for the Chinese people and for the socialist movement worldwide.”

The party and its success story. By Wang Chaohua (New Left Review, Issue 91, January-February 2015). “How should the balance-sheet of Chinese Communism be assessed?”

The road to Tiananmen Square: workers and students (Workers Liberty, 29 December 2010). “Jack Cleary explains why the workers and students are in bloody conflict with China’s ‘socialist’ rulers.”

60th anniversary of the Chinese revolution: A great leap forward? By Simon Gilbert (Socialist Review, Issue 341, November 2009). “Post-revolutionary China needed rapid industrialisation to meet the demands of the middle class and compete with other capitalist states, but it was the workers and peasants who paid the price.”

How Mao conquered China: Writings from the US Trotskyist movement, 1948-49. By Jack Brad (Workers’ Liberty, Vol.3, No.24, October 2009, 16 p.). “This selection of the contemporary coverage published in the weekly Labor Action was made by Hal Draper in 1970.”

Who made China’s revolution? By Dennis Kosuth (SocialistWorker.org, October 13, 2009). “As China celebrates six decades as a supposed ‘peoples’ republic’, Dennis Kosuth looks at how the struggle for workers’ revolution in China was derailed.”

When China threw off imperialism. By Charlie Hore (Socialist Review, Issue 340, October 2009). “The 60th anniversary of the Chinese Revolution will be marked by the customary orchestrated celebrations in Tiananmen Square. In the first of a short series on China, Charlie Hore looks at how the revolution came about and its impact on the world.” See also Charlie Hore: Will this be China’s century? (Issue 343, January 2010).

The roots of Chinese Stalinism. By Per-Åke Westerlund (Socialism Today, Issue 132, October 2009). “While modelled on Stalin’s Russia, the new regime had its own, independent genealogy. Per-Åke Westerlund looks at how the Chinese variant came into being.”

The Chinese Revolution of 1949, Part One. By Alan Woods (In Defence of Marxism, 1 October 2009) + Part 2 (7 October 2009). “For Marxists the Chinese Revolution was the second greatest event in human history, second only to the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.”

Sixty years after the Chinese Revolution: Lessons for the working class. By John Chan (World Socialist Web Site, 1 October 2009). “Despite the immense scale of the struggle, however, the 1949 revolution was not socialist or communist. It did not bring the working class to power, but the peasant armies of Mao.”

China, Maoism and popular power, 1949–1969. By Pierre Rousset (Europe Solidaire Sans Frontiéres, 1 May 2008). “This essay has been published in The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. Vol.2. Blackwell Publishing, 2009, p.705-712.”

Chinese Workers: a new history. By Jackie Sheehan (Routledge, 1998, 269 p.; online at Libcom.org). “This book traces the development of workers’ struggles from the 1950s to the Tianenmen movement of 1989 and beyond.”

Revolutionärerna i Kinas städer (pdf). Av Gregor Benton (Marxistarkiv.se). Uddrag (s.1-123) af China’s Urban Revolutionaries: Explorations in the History of Chinese Trotskyism, 1921-1952 (Humanities Press, 1996, 269 p.). See also Gregor Benton: Explorations in the history of Chinese Trotskyism (pdf) (IIRE Working Papers, Issue 26, 1992, 50 p.) + Gregor Benton (ed.): Prophets Unarmed: Chinese Trotskyists in Revolution, War, Jail, and the Return from Limbo (Brill, 2015/Haymarket Books, 2017, 1269 p.); and review by Charlie Hore: Trotskyism in China (International Socialist Review, Issue 111, Winter 2018-19). “This magisterial work, building on materials both previously translated and written by the editor, should do much to reverse that lack of knowledge. It is an inspiring story of perseverance against unimaginable odds to keep alive a revolutionary tradition.” + review by Promise Li: China’s Unarmed Prophets (Against the Current, Issue 225, July-August 2023). “The publication of Prophets Unarmed represents a significant milestone, gathering some of the most important primary and secondary sources on the Chinese Trotskyists’ activities in an authoritative edition.”

China: 1949-1989-2019. By Jack Cleary (Solidarity & Workers’ Liberty, Issue 519, 2 October 2019). “This is taken from an article in Workers’ Liberty 12-13, 1989, omitting the current affairs comment on 1989 and its immediate background, and amended very slightly (tenses, etc.).”

The Chinese Revolution. By Pierre Rousset (IIRE Notebook for Study and Research, No.2, January-May 1987, 39 p. + No.3, May 1987, 75 p.). Part 1: The Second Chinese Revolution and the shaping of the Maoist Outlook; Part 2: The Maoist Project Tested in the Struggle for Power.

The mandate of heaven: Marx and Mao in modern China. By Nigel Harris (Quartet Books Limited, 1978, 307 p.; online at REDS – Die Roten). Contents: The long march to victory – The People’s Republic – Workers and peasants in the People’s Republic – Equality, democracy and national independence – Proletarian internationalism – The Chinese Communist Party and Marxism.

China and world revolution. By Nigel Harris (International Socialism, No.78, May 1975, p.7-27). Contents: China: Imperial and Republican – China and Economic Development – The Nature of the Regime – The Chinese Regime – China’s Policies Abroad – World Crisis.

The causes of the victory of the Chinese Communist Party over Chiang Kai-Shek, and the CCP’s perspectives. By Peng Shuzhi (World Socialist Web Site, 3 October 2019). “The report below on the 1949 Chinese Revolution was delivered by the Chinese Trotskyist Peng Shuzhi to the Third Congress of the Fourth International in 1951.” See Introduction by Peter Symonds (ibid.).

How Mao conquered China: Writings from the US Trotskyist movement, 1948-49 (Workers Liberty, Vol.3, No.24, October 2009, 16 p.). With Hal Draper’s original introduction to the 1970 edition. All the articles were written by Jack Brad.

Se også:

- Chinese Communism (Marxists Internet Archive). Who is who – Documents – Peking Review – Music – Image gallery.

- China / Chinese Trotskyism (Marxists Internet Archive)

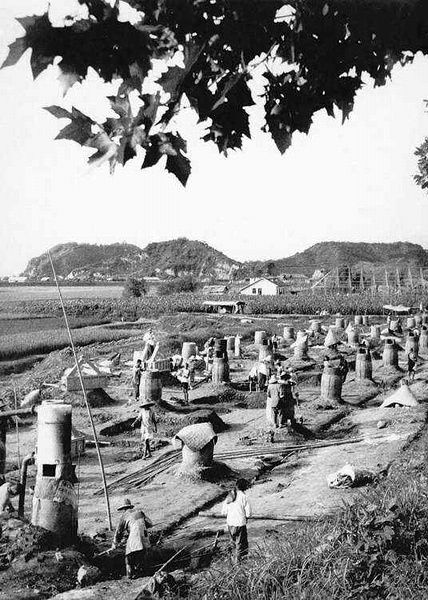

Det Store Spring Fremad: januar 1958

Lederen af Kinas Kommunistiske parti Mao Zedong lancerer den 2. fem-årsplan, indeholdende det såkaldte “Store Spring Fremad”.

På partikonference i Beijing januar 1962, “de syv tusindes konference”, betegner præsident Liu Shaoqi kampagnen som skyld i den efterfølgende hungersnød og økomiske krise, der var “30% naturens, 70% menneskers skyld”.

- Det store spring fremad (Wikipedia.dk)

- Great Leap Forward (Wikipedia.org)

- Great Chinese Famine (Wikipedia.org)

China: worse than you ever imagined. By Ian Johnson (The New York Review of Books, Vol.59, No.18, November 22, 2012). Review of five books about the great famine.

50 years after: The tragedy of China’s ‘Great Leap Forward’. By John Riddell (Socialist Voice, April 20, 2009). “In the early 1980s, the Chinese government released demographic statistics pointing to 15 million famine-related deaths. Writers hostile to the People’s Republic claim this is an understatement, offering estimates as high as 38 million.”

Did Mao really kill millions in the Great Leap Forward? By Joseph Ball (Monthly Review, September 21, 2006). “The approach of modern writers to the Great Leap Forward is absurdly one-sided.”

Revisiting alleged 30 million famine deaths during China’s Great Leap. By Utsa Patnaik (MR Online, June 26, 2011). “Thirty years ago, a highly successful vilification campaign was launched against Mao Zedong, saying that a massive famine in which 27 to 30 million people died.”

China’s great famine: 40 years later. By Vaclav Smil (British Medical Journal, December 18, 1999). “We will never know the precise number of casualties, but the best demographic reconstructions indicate about 30 million dead.”

The great Mao mystery (The Guardian, 27 November 1999). Review of Jonathan Spence’s Mao (1999) + Philip Short’s Mao: A Life (1999). “China’s dictator was never wrong as biographies of Mao from Philip Short and Jonathan Spence reveal. Millions died, says Nigel Harris, to prove the point.”

The Great Leap Forward and after. Chapter 4 in Nigel Harris: The Mandate of Heaven (London, 1978, s.48-59; online at REDS – Die Roten)

Litteratur:

Den ukendte historie om Maos Store Sult. Af Rana Mitter (Information.dk, 22. december 2012). Anmeldelse af Yang Jisheng: Tombstone: The Great Chines Famine, 1958-1962 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012). “Nyt historisk værk om den kinesiske ledelses medskyldighed i den store hungersnød er blevet en politisk sensation i Kina.”

Maos store hungersnød: Den største katastrofe i Kinas historie, 1958-62. Af Frank Dikötter (Informations forlag, 2011, 478 s.). Se anmeldelser mv.:

- Mao’s Great Famine (Wikipedia.org)

- Maos hungersnød var ikke noget teselskab (pdf). Af Chris Holmsted Larsen. (Arbejderhistorie, nr. 1, 2013, s.96-98). “Når man har læst Dikötters anbefalelsesværdige bog, så står én ting lysende klart; i Maos Kina sultede folk ikke bare ihjel – de blev sultet ihjel.”

- Anmeldelse af Ida Munk (Historie-online.dk)

- Hungersnød i socialismens navn. Af Bjarne Nielsen (Arbejderen.dk, 19. april 2012)

- Var Maos ondskab skyld i hungersnød? Af Hatla Thelle (Modkraft.dk/Kontradoxa, 10. januar 2012)

- Review by Aaron Leonard (Logos, Vol.10, No.4, 2011)

- Great Leap into famine: a review essay (pdf). By Cormac O Gráda (Population and Development Review, Vol.37, Issue 1, March 2011, p.191-210; online at Researchgate.net/Internet Archive)

- ‘Mao’s famine’ – because imperialism never starved anyone to death. Some initial comments by Joseph Ball (Marxist Update, February 24, 2011)

- Mao’s great famine. By Jonathan Fenby (The Guardian/The Observer, 5 September 2010)

Hungry Ghosts: China’s Secret Famine. By Japser Becker (John Murray, 1996, 352 p.). See review by Nicholas Eberstadt: The great leap backvard (The New York Times, February 16, 1997). “The story behind Mao’s policies of the late 1950’s, which led to the starvation of tens of millions.”

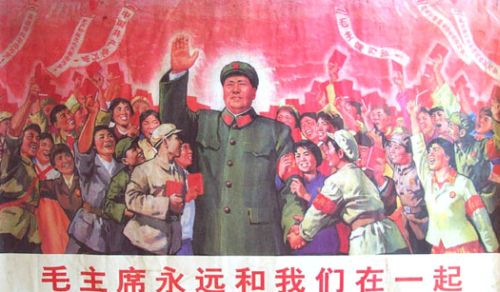

Den Proletariske Kulturrevolution: august 1966

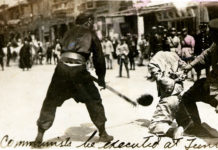

Efter Formand Mao Zedong’s vægavis “Bombarder Hovedkvarteret” (5.8.1966) (se udg. på engelsk) vedtager Kinas Kommunistiske Partis Centralkomites 11. plenum 16 punkter om “Den store proletariske kulturrevolution” (se udg. på engelsk).

og ca. 20. mio. rødgardister slippes løs på kultur- , uddannelses- og partiinstitutioner i byerne under “Kulturrevolutionen”.

Se:

- Kulturrevolutionen (Denstoredanske)

- Kulturevolution, den kinesiske. Af Erik Nord (Leksikon.org)

- Kulturrevolutionen i Kina. Af Jesper Samson (FaktaLink, marts 2016)

- Cultural Revolution (Marxists Internet Archive; Glossary of Events)

- Cultural Revolution (Wikipedia.org). With external links.

- Morning Sun: A film and website about Cultural Revolution.

- 50 years ago: “Cultural Revolution” begins in China (World Socialist Web Site, 15 August 2016)

Det kulturrevolutionære drømmeland: en analyse af danske rejseberetninger fra kulturrevolutionens Kina 1966-1976 (pdf). Af Erik Kjærgaard (Arbejderhistorie, nr.3, 2000, s.1-21). “… artiklen [forsøger] at blotlægge de dybereliggende årsager til fascinationen, der både omfatter kinesernes systematiske manipulation med de rejsende og forfatternes ideologiske selvbedrag.”

Kinas blodige mareridt: Maos kulturrevolution. Af Carsten Lorenzen + Charlie Hore (Socialistisk Arbejderavis, nr. 22, september 1986). “For mange på venstrefløjen var Kina og kulturrevolutionen en stor inspirationskilde … Virkeligheden var anderledes.”

A hidden struggle: China’s Cultural Revolution in 1968. By Charlie Hore (Verso, Blog, 21 May 2018). “China’s Cultural Revolution was a key reference point for huge numbers of activists in 1968, but by then the CR was all but over.”

The Cultural Revolution. Chapter in Charlie Hore: China: Whose Revolution? (Socialist Workers Party, 1987, p.20-27). På dansk: Kulturrevolutionen (Kina 1949: Folkets revolution?, Internationale Socialisters Forlag, 1989). “I virkeligheden var Kulturrevolutionen en blodig og ondskabsfuld magtkamp i den herskende klasse.”

The Cultural Revolution. Chapter 5 in Nigel Harris: The Mandate of Heaven (London, Quartet Books, 1978, p.60-72; online at REDS – Die Roten). “The Cultural Revolution was important in revealing the reality of China. The twin bases of power, the PLA and the party, survived intact.”

China: Let a hundred flowers bloom or ‘a host of dragons without a leader’. By Nigel Harris (International Socialism, No.35, Winter 1968/1969). “The Cultural Revolution was an attempt by a section of the central Party leadership to re-establish central control over the whole country, perhaps as a prelude to accelerating the rate of overall economic growth.”

Two years of the Cultural Revolution. By K.S. Karol (The Socialist Register, 1968, p.55-86). “… the rival groups which, we are told, are at each other’s throats still proclaim their fidelity to the same man, Mao Tse-tung, and to the same Party, the Chinese CP.”

The Cultural Revolution: an attempt at interpretation. By Ernest Mandel (International Socialist Review, Vol.29, No.4, July-August 1968). “Mao’s attempt at reforming the bureaucracy without having the masses question the whole of the bureaucratic regime has failed.”

Crisis in China. By Tony Cliff (International Socialism, No.29, Summer 1967). “To understand the forces behind the Cultural Revolutions lone must start by analysing the socio-economic problems with which China is wrestling.”

Cultural revolution or Maoist reaction? By Raya Dunayevskay (New Politics, Spring 1967, p.24-36). “Now that the Cultural Revolution has slowed its pace, there is time to take a closer look at this startling phenomenon.”

China: What price culture? By Nigel Harris (International Socialism, No.28, Spring 1967). “What is happening in China has been, so far, irrelevant to the poverty of the mass of the population: it is relevant only to which group rides the ruling class.”

Tragedy of China’s Cultural Revolution (1966). By Raya Dunayevskaya (News & Letters, August-September 2006). “Even a cursory look at the actual, instead of the imagined, developments in Mao’s China will show that power in the People’s Republic does not lie in the hands of the people.”

Den Stora Kulturrevolutionen (1966). Av Isaac Deutscher (Marxists Internet Archive, Svenska arkivet). “När man läser de ändlösa rapporterna om ‘massornas kulturella uppror’ i Kina, kan man frestas att avfärda upproret som en ren fars.”

Litteratur:

Peking og de nye venstrebevægelser: analyser af dokumenter og taler. Af Klaus Mehnert (Fremads Fokusbøger, 1970, 173 sider)

Kulturrevolutionen i Kina: En antologi. Red. Ellen Bruun og Jacques Hersh (Bibliotek Rhodos, 1969, 248 sider)

Kina nu. Red. Ruth Adams (Gyldendal, 1967, 298 sider). Heri: ‘Den store proletariske kulturrevolution’, af J.B. Holmgaard (side 103-129)

Se også:

Cultural Revolution Campaigns (Chineseposters.net)

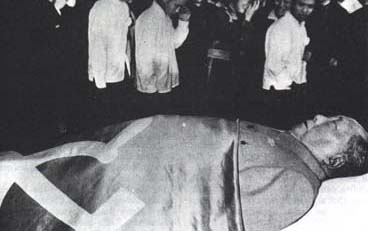

Mao dør: 9. september 1976

Formanden for det Kinesiske kommunistparti, KKP, Mao Zedong dør i B Beijing. (Født 26.12.1893 i Shaoshan, Xiangtan amtet, Hunan-provinsen ), leder af Kinas Kommunistiske Parti.

Se:

- Mao Tse-Tung (Leksikon.org)

- Mao Zedong (Denstoredanske)

- Mao Zedong (Marxists Internet Archive; Reference writers). Biography – Works – Poetry – Images.

- Mao Zedong (Wikipedia.org)

- History of the People’s Republic of China, 1976–1989 (Wikipedia.org)

Bookwatch: China since Mao. By Charlie Hore (International Socialism, Issue 67, Summer 1995). “These [books] break down into three broad categories: Western journalism, Western academic studies and writings from within China. I intend to look at each of these categories in turn, before discussing the revolt of 1989 and the literature it has produced.”

Rystende beretning om Maos Kina ligger langt fra blåøjede Whiskybælte-kollektiver. Af Claus Bryld (Politiken.dk, 20. oktober 2013). Anmeldelse af Torbjørn Færøvik, Maos rige: en lidelseshistorie (Forlaget Sohn, 2013, 573 s.). “Storhedsvanvid og undertrykkelse præger historien om Mao og det morderne Kinas tilblivelse.” Kun online for abonnementer.

The myth of Mao’s ‘anti-imperialism’. By Parson Young (In Defence of Marxism,

Understanding China after Mao (RS21, 10 January 2023). “Charlie Hore reviews Frank Dikötter’s China after Mao [Bloomsbury, 2022], finding a work with large omissions which fails to explain why China has changed so much since the 1970s.”

On Contradiction: Mao’s party-substitutionist revolution in theory and practice. Part 1-4. By Richard Smith (New Politics, June 7 – July 29, 2022). “Explaining and debunking the theory and practice of Maoism.”

Remembering the riots of spring 1976 in China. By Charlie Hore (RS21: Revolutionary Socialism in the 21th Century, April 9, 2016). “It’s 40 years since workers, students and school-students broke the oppressive regime that had come out of the Cultural Revolution in China …”

On Mao’s contradictions. By Tariq Ali (New Left Review, Issue 66, November-December 2010). Review of Rebecca E. Karl, Mao Zedong and China in the Twentieth-Century World (Duke University Press, 2010, 216 p.). “Karl gives admirably succinct accounts of the main tensions and debates that ran through the Maoist period …”

Mao: The Untold Story. By Jung Chang and Jon Halliday (Jonathan Cape, 2005; dansk udgave: Mao: den ukendte historie, Rosinante, 2005, 889 s.). See reviews:

- Was Mao really a monster?, Introduction in: Was Mao really a monster? The Academic Response to Chang and Halliday’s ‘Mao: The Unknown Story’. Edited by Gregor Benton and Lin Chun (Routledge, 2010, p.1-11 + 187-189; online at Europe Solidaire Frontiéres). Se uddrag på svensk: Var Mao verkligen ett monster? (pdf) (Marxistarkiv.se, 29. september 2020, 82 s.). “Vi har här översatt redaktörernas introduktion och 7 av recensionerna från bokens engelska upplaga.”

- Mao out of context. By Charlie Hore (International Socialism, Issue 110, Spring 2006)

- Maos magt. Af Hatla Thelle (Modkraft.dk, 15. februar 2006)

- Jade and plastic. By Andrew Nathan (London Review of Books, Vol.27, No.22, 17 November 2005). På dansk: Skidt og kanel (Det Ny Clarte, nr.1, november 2006, s.57-60). P.t. ikke online.

- Mao in question. By Phil Hearse (International Viewpoint, Issue 369, July-August 2005)

- Mao: The end of the affair. By James Heartfield (Spiked, 4 July 2005)

- The myth of Mao. By Chris Harman (Socialist Worker, Issue 1956, 18 June 2005)

The great Mao mystery. By Nigel Harris (The Guardian, 27 November 1999). Review of Jonathan Spence’s Mao (Weidenfeld, 1999, 205 p.) + Philip Short’s Mao: A Life (Hodder and Stoughton, 1999, 782 p.). “Philip Short’s volume is, despite its length, wonderfully readable and rich in background material and eyewitness accounts … Jonathan Spence covers the same ground confidently and with authority.”

China since the Cultural Revolution. By George Gorton (International Socialism, Issue 23, Spring 1984, p.43–75). “For us the direction that China has taken since Mao’s death is not ‘revisionism’ or a ‘betrayal of principles’, but rather the necessary response of a ruling class to their own and the world’s economic crises …”

The mandate of heaven: Marx and Mao in modern China. By Nigel Harris (Quartet Books, 1978, 307 p.; online at REDS – Die Roten). “Using publications from the People’s Republic and his own extensive research, Nigel Harris has written a serious critique of the history, aims and actions of the communist Party in China.”

Mao Tse-tung. By Nigel Harris (International Socialism, No.92, October 1976, p.3-20). Contents: Mao and the Chinese Revolution – The Communist International and China – The Making of Mao – Mao Tse-tung Thought – Mao and the People’s Republic – Prospects.

Mao Tse-Tung and Stalinism. By Tony Cliff (Socialist Review, April 1957). “… to anyone using the Marxist method of analysis, which looks at the economic foundation of politics, Mao’s extreme Stalinism is not unexpected.”

Se også:

- Linkbox: China and Capitalism (Socialistisk Bibliotek). Om Kinas nyere udvikling.

Kvindeoprør – fra fabrikken Røde Stjerne til Hollywood. Af Vibeke Nielsen (Solidaritet.dk/Kritisk Revy, 24. september 2024). “I anledning af 75-året for den kinesiske revolution 1. oktober, bringer vi på Kritisk Revy her en beskrivelse af, hvordan den danske kvindebevægelse blev inspireret af udviklingen i Kina.”

Let a hundred flowers wither: the many failures of Western Maoism (Marxist Left Review, Issue 28, March 2025).”April Holcombe discusses the destructive influence of Maoism in the West, and how it derailed the development of a genuinely revolutionary anti-Stalinist left. In the 1960s and ’70s.”

China and Trotskyism: Marxist discussion on China, 1929-2017. Edited by Paul Hampton (Workers Liberty, 2023, 48 p.). “These articles from the Trotskyist tradition about Maoist China provides a unique perspective that has long been buried. The Chinese Communist Party was an authentic workers’ party in the 1920s, until misguided by Stalinism and exterminated by the Guomindang. These leading communists became Trotskyists after the failed 1925-27 revolution.”

Looking back at Maoism and the global Left. By Kevin Anderson (New Politics, No.70, Winter 2021). Review of Julia Lovell, Maoism: A Global History (Knopf, 2019, 624 p.). “[Lowell’s book] is the product of archival research, of participant interviews, and of a careful synthesis of previous scholarship. Lovell is not part of the radical left but an academic historian whose book is nonetheless of paramount importance for us. And some of her findings are eye-opening.” See also review by Tony Phillips (Socialist Review, Issue 449, September 2019) + review by Alex de Jong: Maoism and its complicated legacy (Jacobin, November 30, 2019).

One hundred years since the May 4 movement in China. Part 1-2. By Peter Symonds (World Socialist Web Site, 4-6 May 2019). “The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was founded in July 1921, little more than two years after the first Beijing protest. Many of the founding members were youth who had been radicalised by the May 4 movement.”

Demystifying Maoism. By Dan La Botz (New Politics, June 15, 2016). Review of Elliott Liu, Maoism and the Chinese Revolution: A Critical Introduction (PM Press, 2016, 148 p.). “Elliott Liu has written an excellent little book that examines Mao Tse-Tung’s role in the Chinese Revolution in an attempt to find out what Maoism really represented for the Chinese people and for the socialist movement worldwide.”

Notes towards a critique of Maoism. By Loren Gouldner (Insurgent Notes, Issue 7, October 2012). “The following was written … primarily to provide a critical-historical background on Maoism for a young generation of militants who might be just discovering it.”

![George Habash square [Tulkarem?], Taken on 7 April 2011, Source: https://www.panoramio.com/photo/50717122. Author: Mujaddara. (CC BY-SA 3.0)](https://socbib.dk/wp-content/uploads/2007/05/George_Habash_sq_-_panoramio-218x150.jpg)