Socialistisk Biblioteks Tidslinje med links til begivenheder og personer i 1789.

Se også Index over personer, organisationer/partier og værker (som bøger, malerier, mm.), steder, begivenheder, mv., der er omtalt på hele Tidslinjen, titler og indhold på emnelisterne osv.

28. april 1789

Under ledelse af Fletcher Christian begår mandskabet på det britiske HMS Bounty mytteri mod kaptajn Bligh.

Se:

- Bounty (Denstoredanske.dk). Kortere dansk intro.

- Mytteriet på Bounty (Wikipedia.no). Lidt længere norsk.

- Mytteriet på Bounty. Af Björn Lundberg (Alt om Historie, nr.3, 2008)

- Mutiny on the Bounty (Wikipedia.org). Med links.

- Mutiny on the Bounty (fiction) (Wikipedia.org). Novels, films, stage etc.

Litteratur:

- Mytteri. Af Ch. Nordhoff og J.N. Hall (Gyldendal, 1934). Senere udgaver med titlen Mytteri på Bounty.

- I kamp med havet. Af Ch. Nordhoff og J.N. Hall (Gyldendal, 1935)

- Pitcairn-øen. Af Ch. Nordhoff og J.N. Hall (Gyldendal, 1936)

Se også:

Paradises lost. By Jared Diamond (Discover Magazine, November 1, 1997; online at Internet Archive). “When the mutineers from HMS Bounty landed on Pitcairn Island, they found no people–just a desolate land marked by the relics of a vanished society. The story of that lost civilization is just now being learned. And it’s far more frightening than any tale of Captain Bligh.”

Se også på Socialistisk Bibliotek:

Tidslinjen 25. september 1764, om mytteri-lederen Fletcher Christian.

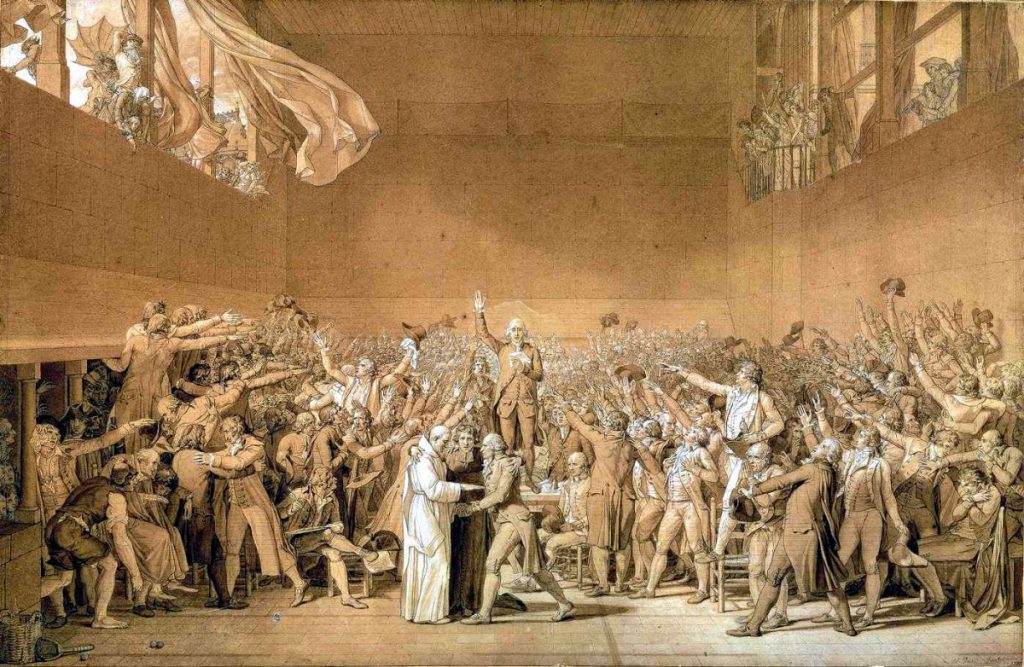

20. juni 1789

“Boldhuseden” er første oprørsskridt i den franske revolution, da kongens indkaldte stænderforsamling (mødtes fra 5. maj 1789) var blevet lukket, og tredje stand ved møde i Boldhuset (tennisbaner) erklærede sig som “grundlovsgivende forsamling” og svor at ville blive til Frankrig havde fået en forfatning.

Links:

Boldhuseden (Denstoredanske.dk)

Tennis Court Oath (Wikipedia.org) med links til bl.a. norske artikel og til Estates General of 1789

Se også på Socialistisk Bibliotek:

Linkbox: Oplysningstiden / The Enlightenment

14. juli 1789

Den Franske Revolution træder ud over stænderforsamlingerne med opstanden i Paris og massernes erobring af fængselsslottet Bastillen i Paris.

The French Revolution develops beyond the Estates-General with the rebellion of the masses in Paris and the Storming of the Bastille.

På dansk:

- Tidslinje 1788-1797. I: Den franske revolution. Red. Mikkel Thorup mfl. (Slagmark, 2015, 271 sider) (Slagmarks Revolutionsserie).

- Bastillen (Denstoredanske).

- Den Franske Revolution (Denstoredanske).

- Den franske revolution. Af Kåre D. Tønnesson (Leksikon.org).

- Miniforedrag – Den Franske Revolution og Danmark. Af Bertel Nygaard (Danmarkshistorien.dk, 8. november 2011, 3 min.) + Video på YouTube.com

- Den franske revolution – 1789 (Perbenny.dk). Den franske revolution – 1789 – Fra den borgerlige til den proletariske Revolution – Den store franske Revolutions Betydning for Eftertiden.

Den franske Revolution. Kap. 4 i Gustav Bang: Brydningstider i Europas historie (Forlaget Fremad, 1945; online på Marxisme.dk).

Tidsdoku. Den franske revolution – parlamentarisme versus direkte demokrati. Af Alfred Lang (Autonom Infoservice, 10. juli 2021). “På tærsklen til sommerpause vil vi for den historieinteresserede del af vores læsere bidrage til et dybere indblik i de dramatiske begivenheder op til og under den franske revolution.”

Frihed, Lighed og Broderskab: Den franske revolution, del I (1789-1792). Af Charlie Lywood (Socialistisk Arbejdervis, nr. 387, juni 2021, s.3) (Almindelige menneskers historie, 17). “Den franske revolution, som brød ud i 1789, startede i Europa en proces, som cementerede det nye opstigende, kapitalistiske borgerskab som magthaver i de dominerende økonomiske og politiske lande i verden.”

Del II: ”La Terreur”: Den franske revolution del II (1793-1794) (nr. 388, august 2021, s.3) (Almindelige menneskers historie, 18). “For Jakobinerne var alliancen med masserne det nødvendige onde mod kontrarevolution. Men de repræsenterede også den klasse, som revolutionen var sat i gang for at sikre – borgerskabet.”

Del III: “Thermidor” og efter: Den franske revolution del III: (1794-1799) (nr. 389, september 2021, s.3) (Almindelige menneskers historie, 19). “Revolutionen … bestod også af millioner af mennesker … som for første gang skabte deres egen historie [og] lærte at slås for deres egne interesser … almindelige mennesker var begyndt at skabe historiens gang”.

Tidsdoku: Den franske revolutions ups and downs (Autonom Infoservice, 30. juni 2020). “Mellem maj og oktober 1789 brød det gamle parasitære Ancien Régime sammen og den borgerlige revolution forandrede på bare fem måneder Frankrig og Europa.”

Retten til at regere sig selv: Revolutionært anti-slaveri i Den Franske og Haitianske Revolution. Af Nicolai von Eggers (Baggrund, 1. oktober 2018). “Denne artikel følger slaveri-debatten fra oplysningens arv i Den Franske Revolution til Haitis og de slavegjortes uafhængighed i 1804.”

1789 som borgerlig revolution: historieskrivning og begrebsbrug hos Georges Lefebvre og Albert Soboul (pdf). Af Bertel Nygaard (Historisk Tidsskrift, bind 107, hæfte 2, 2007, s.478-508). “Måske er det på tide at erstatte den antimarxistiske kulturhistories blinde selvforherligelse med en kyndigere stillingtagen, der giver mulighed for konstruktiv selvkritik.” Se også andre marxister som Albert Mathiez’, Jaures og Daniel Guerin, hvis analyser og begrebsbrug inddrages (se fx. note 75, side 495). Se nedenfor i afsnit: Litteratur.

Frihed, Lighed og Broderskab. Af Lars Ulrik Thomsen (Arbejderen.dk, kronik, 11. januar 2017). “De borgerlige franske revolutioner havde afsmittende virkning på andre lande i Europa.”

In English:

- Historiography of the French Revolution: The Marxist/Classic interpretation (Wikipedia.org). With links to other subject on the French Revolution. See also Appendix below in the article by McGarr.

- The French Revolution (Marxists Internet Archive). With Timeline, Principal Documents, Archives of Writers, Biographies + Revolutionary France Subject Archive.

The French Revolution is still a work in progress (Jacobin, July 14, 2023). An interview with Alexis Corbiere: “Today’s French political leaders are more likely to present the Jacobins as bloody authoritarians than forerunners of modern democracy. But redeeming their legacy is key to understanding the Revolution’s unfulfilled promise.”

The French Revolution was the beginning of the modern world. By Jeremy Popkin (Jacobin, October 5, 2021). “Conservative ideologues have dismissed the French Revolution as an unnecessary bloodbath. But a fresh look at the Revolution shows us its vital relevance to contemporary political issues, from demands for economic equality to the struggle against racism.”

A Guide to the French Revolution. By Jonah Walters (Jacobin, July 14, 2015). “… what was the French Revolution, how did it reshape Europe and the world, and what relevance does it have to the workers’ movement today? Here’s a short primer.”

The top 10 French Revolution novels (The Guardian, 10 July 2023). “Ahead of this year’s Bastille Day, novelist Jonathan Grimwood chooses fiction’s best treatments of the mother of modern revolts.”

The French Revolution: storming of the Bastille. Part 47 in Neil Faulkner: A Marxist History of the World (Counterfire, 3 October 2011).

The French Revolution: the Jacobin dictatorship. Part 48 in Neil Faulkner: A Marxist History of the World (Counterfire, 10 October 2011).

The French Revolution: Thermidor, Directory and Napoleon. Part 49 in Neil Faulkner: A Marxist History of the World (Counterfire, 24 October 2011).

The French Revolution. Part 6, chapter 2 in Chris Harman: A People’s History of the World (pdf) (Bookmarks, 1999, p.277-302; online at IS Tendency/Internet Archive) + Chronology (p.278).

The French Revolution. Chapter 3 in Eric Hobsbawm: The Age of Revolution, 1789-1848 (pdf) (Weidenfield and Nicholson, 1962, p.53-76; online at Libcom.org).

Artikler/Articles:

The French Revolution was the beginning of the modern world. By Jeremy Popkin (Jacobin, October 5, 2021). “Conservative ideologues have dismissed the French Revolution as an unnecessary bloodbath. But a fresh look at the Revolution shows us its vital relevance to contemporary political issues, from demands for economic equality to the struggle against racism.”

The Permanent Guillotine. By Matthew Quest (New Politics, August 31, 2019). Review of Mitchell Abdior, ed. and trans.; The Permanent Guillotine: Writings of the Sans-Culottes (PM Press, 2018, 160 p.). “Mitchell Abidor does a great service to the scholar of radical history and political thought who has little facility in French by translating into English a selection of the writings of the sans-culottes and their spokespeople …”

Yes, the French Revolution was necessary. By Eric Hazan (Jacobin, July 14, 2016). “Historians who argue otherwise overlook the appalling conditions on the ground.” Extract of Eric Hazan, A People’s History of the French Revolution (Verso, 2014, 432 p.). See review by William Alderson (Counterfire, May 7, 2015) + Eric Hazan responds to David Bell’s review of A People’s History of the French Revolution in the Guardian (Verso, Blog, 29 September 2014).

A Guide to the French Revolution. By Jonah Walters (Jacobin, July 14, 2015). “For Bastille Day, we have answers to a bunch of questions about the French Revolution.”

Women in the French Revolution. Chapter 1 in Hal Draper: Women and Class: Towards a Socialist Feminism (Center for Socialist History, 2011, p.7-42, online at Marxists Internet Archive). “… the starting point of an organized movement for demands based on women’s equality … The first time this happened was in the Great French Revolution, particularly in the revolution’s upswing from 1789 to 1793, and above all on its left wing.” See also chapter 2: The Society of Revolutionary Women of 1793 (Ibid., p.43-83).

The French Revolution is not over. By Neil Davidson (International Socialism, Issue 113, Winter 2007, p.159-178). Review of Henry Heller, The Bourgeois Revolution in France, 1789-1815 (Berghahn Books, 2006). “… it is the first book in English explicitly to defend a Marxist interpretation of the French Revolution since revisionism became entrenched.”

The French Revolution: Marxism versus revisionism (International Socialism, Issue 80, Autumn 1998, p.113-125). Review of G Kates (ed.), The French Revolution: Recent Debates and New Controversies (Routledge, 1997). “Paul McGarr gives an overview of debates on the French Revolution.”

The French Revolution (In Defence of Marxism, 22 December 1999). “An article by Alan Woods which was originally written in 1989 … with a new introduction by the author.”

Where will this voyage end? By Neal Ascherson (London Review of Books, Vol.12, No.11, 14 June 1990). Review of E.J. Hobsbawm, Echoes of the Marseillaise: Two centuries look back on the French Revolution (Verso, 1990, 144 p.). “… a history of the Revolution’s history which examines the main interpretations over the past 200 years in the light of today’s revisionist counter-offensive. Professor Hobsbawm displays his past-mastery of sources.”

Marxism and the Great French Revolution (International Socialism, Issue 43, Summer 1989, p. 1-171):

- Paul McGarr: The Great French Revolution (p.15-110). “Paul McGarr’s contribution is so compact that it can be recommended to anyone whose prior knowledge is less than encyclopedic.” With appendix: Historians and the French Revolution (p.89-95).

- Alex Callinicos: Bourgeois revolutions and historical materialism (p.113-171). “Callinicos discusses the various attacks upon and defences of the traditional Marxist class analysis.”

In defence of the French revolution. By Martin Thomas (Workers’ Liberty, Issue 12-13, August 1989, 12 p.). “The French Revolution set the benchmarks for radical and democratic politics, and it was the launch-pad for socialist politics.”

Vive La Revolution: A roundtable discussion (Marxism Today, July 1989, p.24-29). “Romantic nostalgia, bloody terror, or the foundations of modernity? The French revolution is taken apart by Robin Blackburn, Eric Hobsbawm, Martin Kettle, Colin Lucas and Laura Mulvey.”

Defending the French Revolution, 1789-93. By Dave Hughes (Permanent Revolution, Issue 8, Spring 1989, p.75-111). “There is no shortage of academics and journalists trying to make the two hundredth anniversary of the Great French Revolution an orgy of so-called refutations of the Marxist interpretation of the French Revolution.”

Litteratur/Literature:

Den franske revolution. Red. Mikkel Thorup mfl. (Slagmark, 2015, 271 sider) (Slagmarks Revolutionsserie). Kildesamling. Se online: indholdsfortegnelse, forord og tidslinje 1788-1796.

Revolutionen lever og har det godt. Af Michael Seidelin Hansen (Arbejderhistorie, nr.33, oktober 1989, side 2-15; scroll ned). Om historikernes diskussioner af revolutionen + dens betydning for samfundt idag og arbejderbevægelsen.

Arbejdere i alle lande… Red. Gerd Callesen (SFAH, 1990, 70 sider) (SFAH skriftserie, 23). “Seminar den 28. september 1989 i anledning af den franske revolutions 200-årsdag og Internationalernes 125-, 100- og 70-årsdag.” Med bidrag af Gerd Callesen, Niels Finn Christiansen, Knud Knudsen, Uffe Jakobsen, Karl Christian Lammers og Steen Christensen.

Class Struggle in the First French Republic Bourgeois and Bras Nus 1793-1795. By Daniel Guerin (Pluto Press, 1977, 295 p.; online at Licom.org).

Socialist History of the French Revolution (1901). By Jean Jaurès (online at Marxists Internet Archive). See also Ian Birchall’s review of a new edition (Pluto Press, 2015): Jaurès on the French Revolution (Grim and Dim, 2015).

The Great French Revolution 1789-1793. By Peter Kropotkin (Libcom.org) + Kropotkin on the French Revolution. By John A. Dawson (Socialist Standard, No. 67, March 1910; online at WorldSocialism.org)

The French Revolution: A History (Wikipedia.org). With links to online edition of Thomas Carlyle’s book. Dansk udgave: Den franske revolution (Martins Forlag, 1917) (see also on this subject: The French Revolution. By E. Belfort Bax (New Age, 10 November 1910; online at Marxists Internet Archive).

The Crowd in the French Revolution. By George Rudé (Oxford University Press, 1959, 280 p.; online at Internet Archive).

Se også på Socialistisk Bibliotek:

- Tidslinjen 6. maj 1758, om Maximilien Robespierre.

- Tidslinjen 26. oktober 1759, om Georges Danton.

- Tidslinjen 24. april 1792, om kampsangen (nationalsangen) Marseillaisen.

- Tidslinjen 22. august 1795 om forfatningen år III/Constitution de l’an III’

- Tidslinjen 27. maj 1797, om Gracchus Babeuf.

- Tidslinjen 9. november 1799, om Napoleons diktatur/on the dictatorship on Napoleon Bonaparte.

- Linkboxen Oplysningstiden / The Enlightenment

See also on Wikipedia.org:

Underneath it reads on the left:

“LE CRIS FRANCAIS / Des Citoyens de tous états se rencontrant dans les rues / se réunissoient, et poussoient ensemble le terrible cris de / La Liberté ou la Mort.”

And on the right it reads: “Départ pour les frontières d’un Citoyen / Volontaire, accompagné de sa femme, de ses / enfants et d’une parente son cousin Le / serrurier porte le Havresac.”

In other words: The French cry / Citizens of all estates come together in the streets / they gather and shout out unitedly the terrible cry of / Liberty or Death.

A citizen’s departure to the frontiers / A volunteer, accompanied by his wife, his / children and a relative his cousin The / locksmith carries the knapsack.

(Musée Carnavalet).

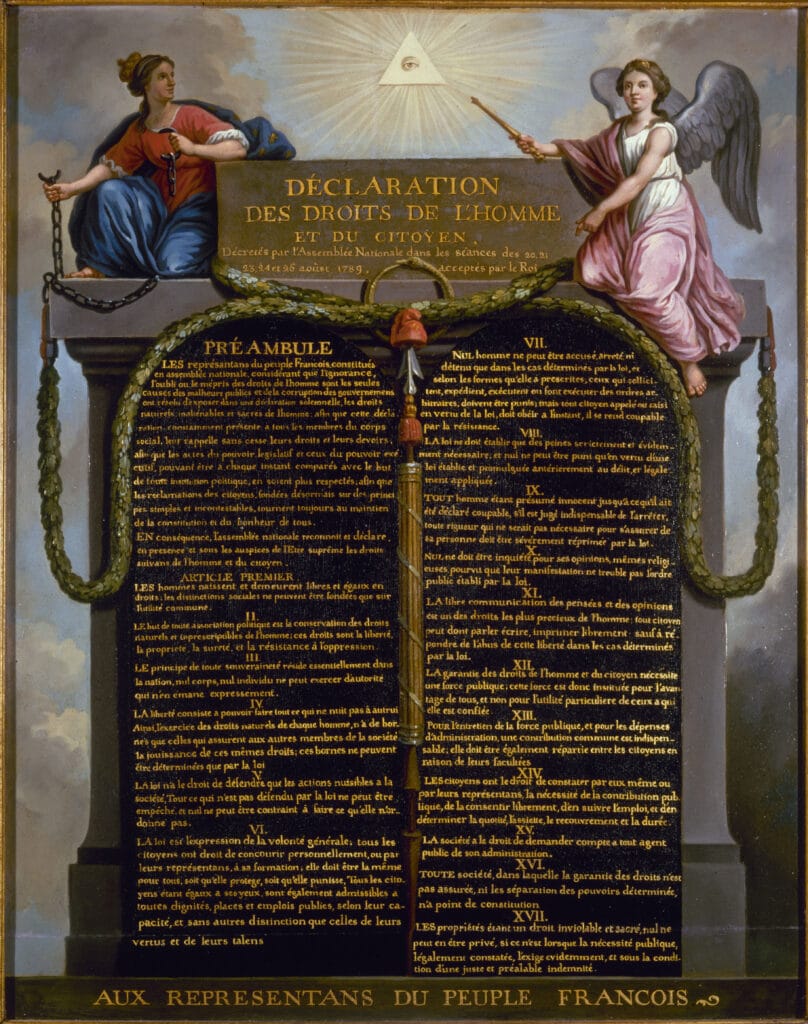

26. august 1789

(Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen) (Erklæringen om Mennesker og borgeres rettigheder).

Den Franske Nationalforsamling vedtager Menneskerettighedserklæringen.

Se:

- Menneskerettighedserklæringen (Denstoredanske.dk)

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (Wikipedia.org)

Se også:

- Menneskerettigheder (Leksikon.org)

- Menneskerettighederne (Wikipedia.dk)

- Institut for Menneskerettigheder (site)

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1793)

Se også på Socialistisk Bibliotek:

Tidslinjen 10. december 1948, om FN’s Menneskerettighedserklæring.